Are All McGings Related?

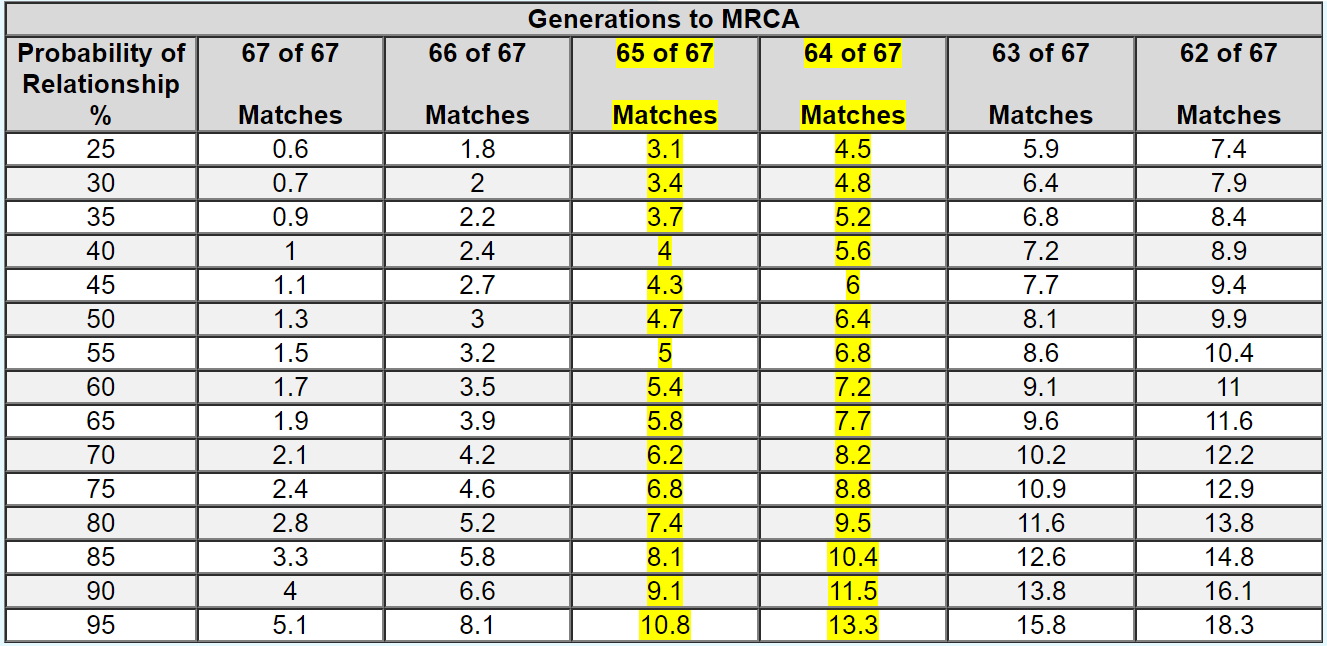

As of December 2019, 4 male McGings have taken a Y-DNA test; 2 at the 111 level, 2 at the 67 level. These 4 are from families that claimed no common relation to each other via standard genealogy records examination. DNA results say that they are indeed related. Based on this information and the best records we can find, it is likely that this common ancestor existed around 1750, which aligns with available data from that period.

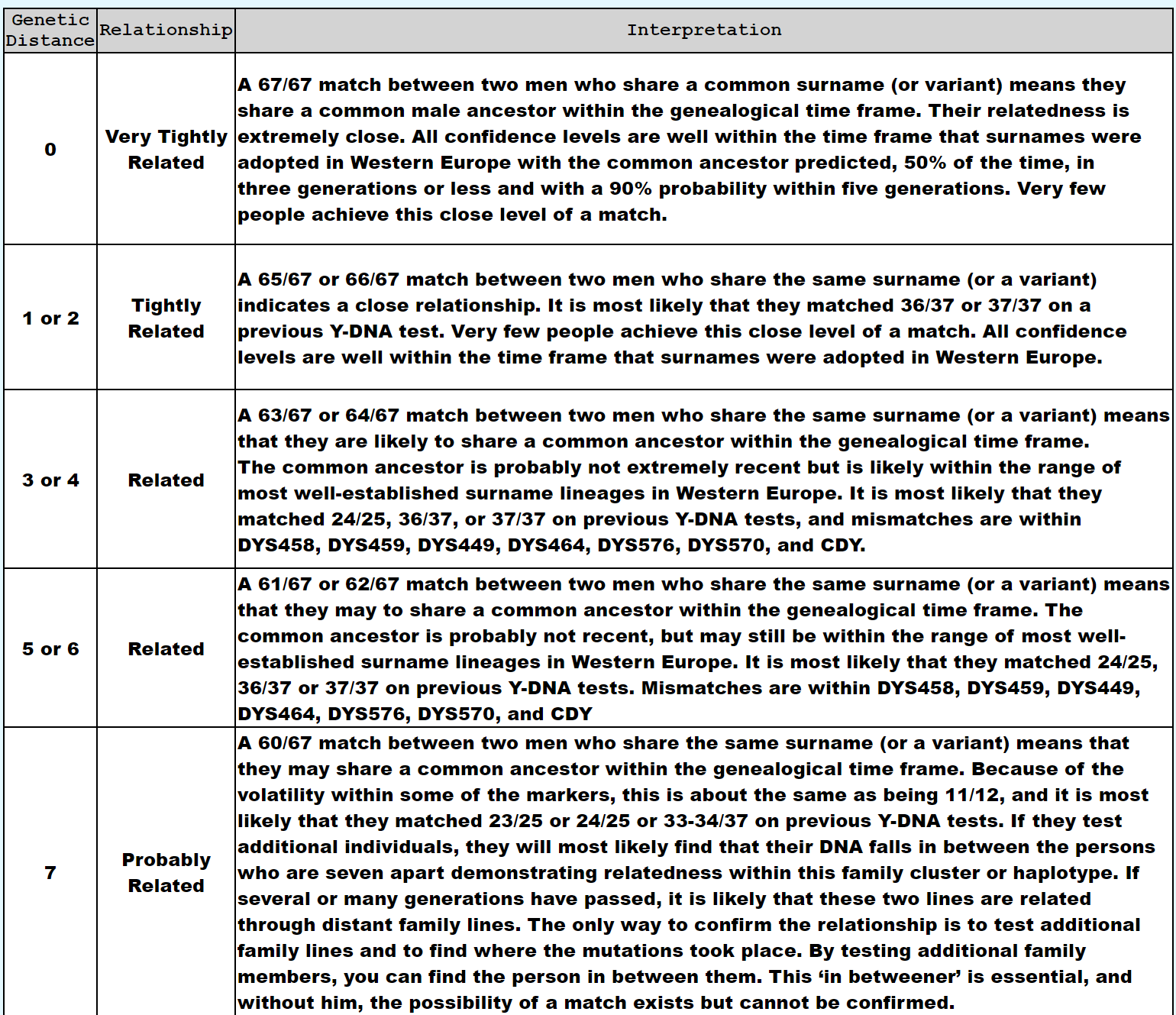

In cultures where surnames are passed from father to son, there is additional evidence beyond a DNA match that two men who share a surname are related. Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA) test results should be interpreted based on both this information and the actual results.

In addition, all tested McGings are of the Y-DNA Haplogroup R-M269 (see Brief Overview of Y-DNA below).

Also, check out the information about X-Matching DNA.

What Are Y-DNA Paternal Lineages Tests?

Your direct paternal lineage is the line that follows your father’s paternal ancestry. This line consists entirely of men. Y-DNA follows the direct paternal line. Your Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA) can trace your father, his father, his father’s father, and so forth. It offers a clear path from you to a known, or likely, direct paternal ancestor.

DNA Matching for Family History

Your Y-DNA may help you find genetic cousins along your direct paternal line. Planned comparisons are the best choice. To set up a planned comparison, select two men who you believe share a direct paternal ancestor. Have both men take a Y-DNA test. If they match exactly or closely, then the DNA evidence supports the relationship. If they do not match, the result is evidence refuting the relationship. When you discover a match outside of a planned comparison, you can still find your common ancestor with matches. To do so, use your known paternal genealogy. For each match, look first for a shared surname if you come from a culture where surnames have followed paternal lines. Then look for common geographic locations on the direct paternal line. Work through each of your ancestors on this line as well as their sons, their sons’ sons, and so forth. Comparing genealogy records is vital when using Y-DNA matching to help you in your research.

The Science of Your Direct Paternal Line

Your Y chromosome is a sex chromosome. Sex chromosomes carry the genetic code that makes each of us male or female. All people inherit two sex chromosomes. One comes from their mother and the other from their father. You and other men receive a Y chromosome from your father and an X chromosome from your mother. Men and only men inherit their father’s Y chromosome. Thus, it follows the same path of inheritance as your direct paternal line. Paternal line DNA testing uses STR markers. STR markers are places where your genetic code has a variable number of repeated parts. STR marker values change slowly from one generation to the next. Testing multiple markers gives us distinctive result sets. These sets form signatures for a paternal lineage. We compare your set of results to those of other men in our database. The range of possible generations before you share a common ancestor with a match depends on the level of test you take. A match may be recent, but it may also be hundreds of years in the past.

Your Ancestral Origins

Our Y-DNA marks the path from our direct paternal ancestors in Africa to their locations in historic times. Your ancestors carried their Y-DNA line on their travels. The current geography of your line shows the path of this journey. You can learn about the basics of your line’s branch on the paternal tree from your predicted branch placement. This information comes from scientists who study the history of populations across geography and time using Y-DNA. They use both the frequencies of each branch in modern populations and samples from ancient burial sites. With these, they are able to tell us much about the story for each branch. This traces back hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of years. Your branch on the tree tells you where your paternal ancestors are present today and about their likely migration paths. This is your Y-DNA haplogroup.

Sidebar – Y-DNA testing versus Autosomal Testing (I.E. Ancestry, FTDNA, 23andme testing)

Y DNA passes down relatively unchanged while autosomal DNA is halved with each generation. Look at the chart on generations following below – the percentage shown is also the amount of autosomal DNA you have of ancestors at those generations. Y-DNA by comparison is passed almost unchanged making it easier to find a common male ancestor. That is why these are two different tests and why one (Y-DNA) costs more than the typical autosomal test that finds cousins.

Remember, except for Y-DNA, in theory, we receive half of the DNA of each ancestor that each parent received. But it’s not exactly half.

DNA is inherited in chunks, chunks that come in different sizes and often you receive all of a chunk of DNA from that parent, or none of it. Seldom do you receive exactly half of a chunk, or ancestral segment – but half is the AVERAGE.

Because we can’t tell exactly how much of any ancestor’s DNA we actually do receive, we have to use the average number, knowing full well we could have more than what the chart says our allocation of that particular ancestor’s DNA, or none that is discernable at current testing thresholds.

The cool thing is that DNA testing can be used to find family and relations and prove that people with a common surname share common ancestors and are thereby blood cousins.